Introduction to variations

Ideally, a test should not be sensitive to changes to the AUT, except when such changes are the subject of the test. Variations help isolate the base test from AUT variability, and lend a great measure of flexibility to your test project.

When an AUT’s low-level functionality or interfaces change – for instance, when an application is updated or adapted to a new hardware platform – you can better maintain the reusability of your tests if you limit changes to variable components that can be swapped in and out without affecting the base functionality of the tests.

TestArchitect aids you in this effort by offering modularity to your test writing. By allowing you to restrict the direct interactions with the AUT to your test modules, actions, interface entities, and data sets, you can often adapt to application changes by making modifications to only these items. With an occasional necessary exception, your test modules can remain intact from one version to the next of your tests.

In this documentation, the terms action and interface are used as a shorthand for user-defined action and interface entity, respectively. Also, because test modules, actions, interface entities, and data sets are defined by their action lines, they are in some contexts referred to as definitions.

In the testing world, you cannot simply evolve your tests to adapt to changing AUTs and environments and leave the past behind. That is to say, every time you adapt a test to a change in a system or platform, you do not necessarily have the luxury of discarding the previous test. Multiple systems and platforms tend to remain valid as testing configurations. And taken together, these factors can combine to form a complex matrix resulting in a very large number of valid testing scenarios.

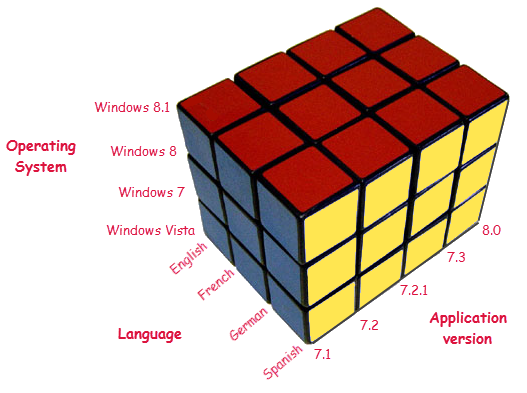

Take for instance, a commercial application that has gone through several upgrades (each of which remains on the market), has been localized for four different language environments, and has been designed to operate with the last four generations of the Windows operating system. A graphical representation of all the resultant possible testing scenarios might look like the following, in which each intersection of lines represents a different configuration.

Granted, not each of this matrix’s 80 points is necessarily a valid test configuration. Nonetheless, there is commonly a need to validate an application’s functionality under a multitude of independent variable factors.

You adapt your test to handle these different factors mostly by modifying the definitions of your test modules, actions, interfaces, and data sets. Typically, some definitions require no changes; others require occasional changes, and still others require frequent changes. Some definitions may be sensitive to changes along one axis of the matrix while not being affected by others.

The idea is that, at any point in time, you may have several different versions of a given action, interface, or data set, any one of which may be needed by your test module for the particular combination of application version, operation system, environment, localization, and more, that your project may be called on to test.

TestArchitect addresses the problem of requiring multiple test configurations by allowing different versions of any given action, interface, or data set to coexist with each other. Each is ready to be called up when circumstances warrant. We use the term variations to refer to these multiple versions of the same action, interface, or data set.

A variation is created when you clone a given definition (known as the default variation) in such a way as to create a relationship between the clone and the original. Subsequently, the cloned definition is modified as required.

The implementation of variations of test modules, actions, interfaces, and data sets in TestArchitect takes two forms: linked variations and keyword variations. In some cases, your choice of which one to employ for a given type of variability in the system/platform mix is a matter of personal preference.

In general, linked variations are the preferred method for addressing what might be termed progressive variability. This is the kind of variability that comes from continuous development or improvement of some aspect of the system/platform mix, such as progressive versions of the AUT itself, or progressive versions of an operating system in which the AUT runs. Linked variations are appropriate when the various versions of a system or platform can be depicted graphically in either a linear form or tree structure. For example, imagine a Car Rental application that has gone through several cycles of development, so that the version history takes this tree form, as is typical in software development:

Keyword variations, by contrast, are perhaps most appropriate when you can define certain categories of distinctions between different system/platform mixes, where the differences are not due to any progressive development or refinement of any aspect of the mix. Different “flavors” of an application, such as different language versions, are a good candidate for keyword variations, as are other localization-based differences, such as differences in date formats, currencies, physical units, etc. Another possible keyword group might involve different market editions of the application, such as a student edition, personal edition, small business edition, or enterprise edition.

In fact, as a matter of practice keywords do usually come in sets. In the case of language, if our application has different versions for, say, US English, UK English, and Spanish, we might define a keyword set of {USEnglish, UKEnglish, Spanish}. If we have tiered editions, we might have another keyword set of {Home, Professional, Enterprise}.

Hence, if we need to test the Spanish version of our application’s Home edition, and the Login window of that version/edition has attributes that require a unique variation of the login interface definition, we might create a variation identified as login {Spanish, Home}.

Note that an application of three languages spread across three editions suggests 3 x 3 = 9 variations for at least some project items. But often it’s the case that the required variability of a given project item is limited. For instance, some windows may vary only by language, not by edition. Or some windows may be identical for US and UK English, but different for Spanish. TestArchitect has ways of simplifying the process of variation creation by taking these commonalities into account, as discussed in Rules for creating variations.

At run time, you provide TestArchitect with the information specifying the versions of systems and platforms in effect for the run (for linked variations), plus the flavor-related info, in the form of pre-established keywords. The automation then uses this information to select the correct set of variations of test modules, actions, interfaces, and data sets to invoke during the run.